Emergency preparedness plans are central to mitigating the public health, social and economic consequences of a pandemic. This article will review existing pandemic preparedness plans and how countries have prepared, in terms of strategy and policy, for a pandemic.

International pandemic response frameworks – guidelines for country plans

Preparedness is the capacity of a health system to prevent, protect and quickly respond and recover from health emergencies. Globally, there are a number of frameworks that have been developed to respond to pandemics. The United States, the country that has the highest score in the global health security index, has developed its own frameworks which are the most country-specific response models in the world. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control has adapted a US framework whilst also considering cross-border threats across the European Union. The United Nations’ Sendai Framework for disaster risk reduction takes a whole-of-society approach. However, instrumental in handling pandemics has been the World Health Organization. Its framework is based on consultation with global stakeholders and was designed to be relevant to health systems globally.

In 1999, the WHO published its first guiding principles for pandemic influenza preparedness. The guide has subsequently undergone several revisions, incorporating the practical experience gained from the response to the outbreaks of avian H5N1 and 2009 H1N1 influenza. In 2005 it published a legal framework for health emergencies, the International Health Regulations (IHR). Whereas the 2003 World Health Assembly adopted a resolution that called for the development of national and global pandemic preparedness plans. In the last update to its guidelines, the WHO stressed the need for each country to conduct a national risk assessment and to adopt or update their national preparedness plans as a result.

Preparedness plans differ from country to country

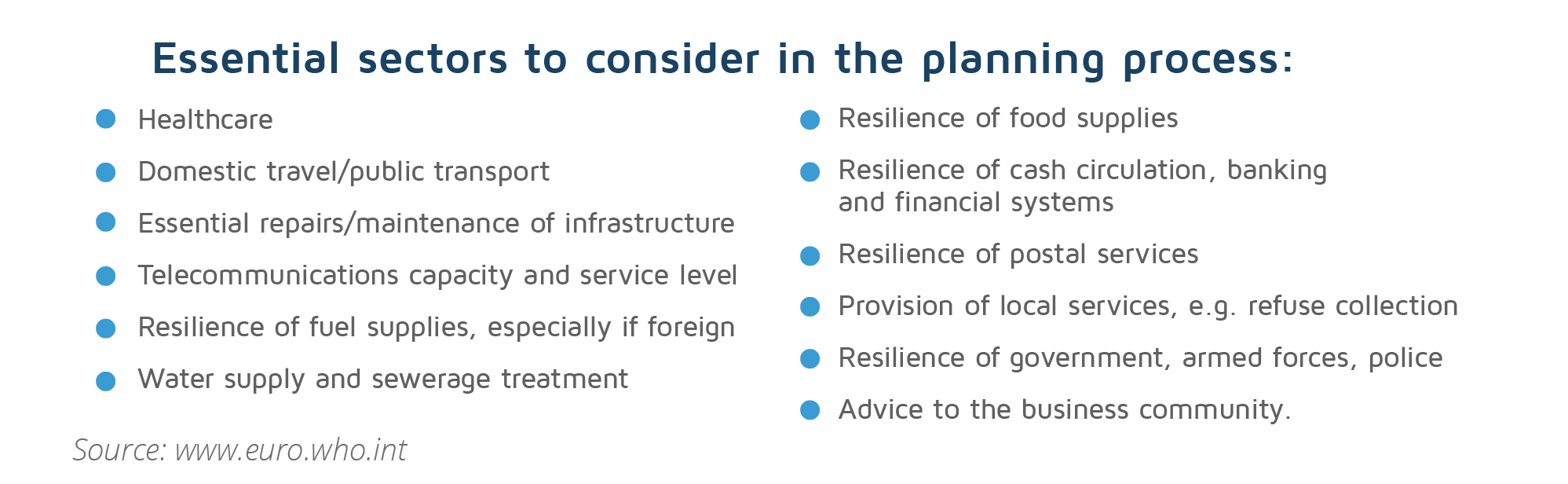

In general, there is variation in the scope and approach of different national plans. Plans can be a discussion of strategy, an action plan or a combination of both. Plans can be developed at different levels within a government and the majority are produced at a ministerial level bestowing the mandate for action upon the respective health ministries. However, some countries adopt a broader approach to pandemics. For example, in the Czech, Finnish, French, Swiss and UK plans, the responsibilities of the whole government are outlined making them the most inter-sectorial preparedness plans in Europe. There can be differences in terms of the strategic goals set by the plans. The protection of the life and the health of the population can be the main strategic goal (as in the case of Denmark and Switzerland), while in other plans the protection of health and societal functions are equally prioritized. Furthermore, some countries, as in Australia’s case, have chosen to produce a preparedness plan specific to the COVID-19 pandemic. A list of all publicly available preparedness plans can be accessed on the WHO website.

Unrealistic and untested- major gaps of preparedness plans

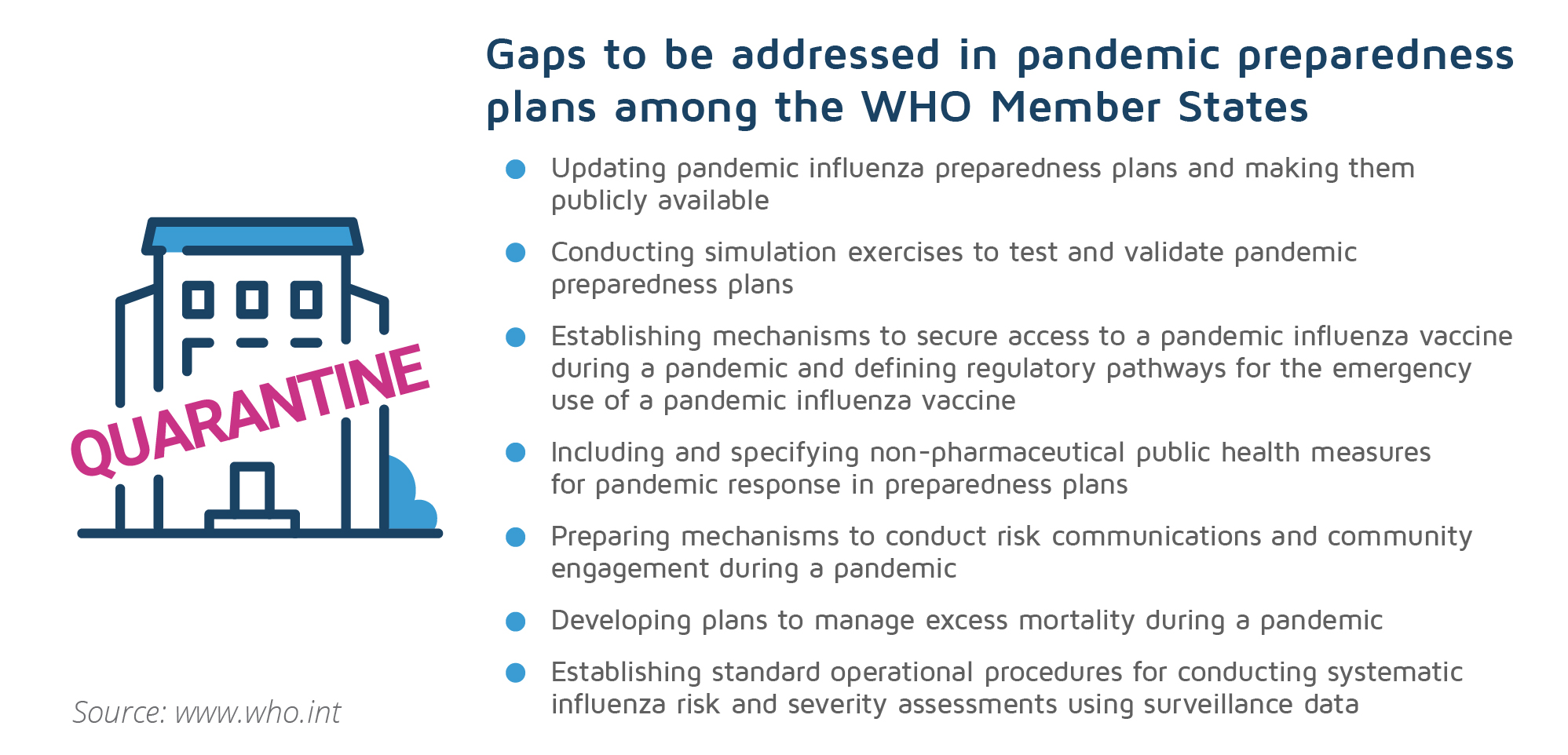

Although a handful of countries have developed national preparedness plans, the level of preparedness worldwide remains unknown. In late 2018, the WHO consulted its 194 Member States through a survey to better understand the current level of pandemic preparedness among them. Globally, 92 of the 104 countries that responded indicated having a national pandemic preparedness plan in place. However, only 42 of the 104 countries (40%) had tested their national pandemic influenza preparedness plans through simulation exercises in the past five years. Member States at all income levels have room for improvement in their pandemic preparedness, especially countries in the African region.

Despite efforts to invest in preparedness, there is no universally accepted method to evaluate preparedness and concerns have been raised that many national preparedness plans may not be realistically feasible. Most assessments of preparedness lack consideration of the capacity to respond which involves the determination of available resources and the capacity to mobilize these. Without this evaluation, the effectiveness and feasibility of any plan remains uncertain and this is being especially true for resource-constrained countries. If a developing state is to focus its scarce resources more efficiently, should the plan focus on prevention, containment, mitigation or recovery? What balance should be struck? Only empirical and contextual evidence can inform national government action, otherwise preparedness plans risk being ill-defined and abstract.

To increase the efficiency of the COVID-19 world response, DevelopmentAid is granting free access to COVID-19-related tenders and grant notices gathered together on its platform.