After a sequence of extremely high rates of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest over the past four years, the annual index has now reached a historic low, falling below 10,000 square kilometers for the first time. From August 2022 to July 2023, a total of 9,001 square kilometers of forest were lost, marking a 22.3% reduction compared to the same period the previous year.

This official Brazilian government data, collected by the Prodes program of the National Institute for Space Research, indicates a departure from the deforestation pattern during the tenure of former President Jair Bolsonaro, which saw an unprecedented decline in the forest, and a shift in direction under the new Brazilian leader.

The change delivers on the electoral promises of incumbent President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva who made a commitment to eliminate deforestation in the biome by 2030.

Environment

In a conversation with the Brazilian press, Environment Minister Marina Silva stated that the previous government had been “lenient” and “complicit” in the crimes committed in the Amazon, particularly illegal mining and deforestation.

For Silva, the deforestation reduction data could be even better had the figures not included the last five months of Bolsonaro’s administration which showed an upward trend in forest devastation.

“We achieved a 22% reduction in deforestation even with an ‘addition’ of 6,000 square kilometers (deforested volume in the Amazon) during the Bolsonaro government,” said the minister.

Environmental expert Beto Mesquita, a member of Coalition Brazil and Director of Forests and Public Policies at BVRio, explained that the decline in the index reflects the change in policies implemented in the first year of the new government. Rural registrations in public forests were cancelled and there was increased surveillance, the destruction of machinery used for deforestation, and even the seizure of cattle on indigenous lands that had been invaded in recent years.

“The reduction in the deforestation rate did not occur randomly. The data indicates that it was a consequence of a set of actions taken by the federal and state governments, especially through their coordination,” Mesquita said.

Why does it matter?

The Amazon plays a crucial role in stabilizing the global climate but, due to wildfires and deforestation, the forest has been emitting more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than it can absorb. A 2021 study published in Nature warns of at least 0.29 billion tons of excess pollutants.

Despite this alarming data, the Amazon Rainforest, far from being unproductive, generates immense quantities of water for the rest of the country. The so-called “flying rivers”, formed by air masses loaded with water vapor generated by evapotranspiration in the Amazon, carry moisture from the Amazon Basin to the rest of Brazil and also influence rainfall in Bolivia, Paraguay, Argentina, Uruguay, and even the southernmost part of Chile.

According to studies by the National Institute for Amazonian Research, a tree with a 10-meter diameter canopy can release over 300 liters of water into the atmosphere in the form of vapor per day – more than twice the amount of water used daily by a Brazilian. A larger tree, with a 20-meter diameter canopy, can transpire over 1,000 liters per day, pumping water and bringing rain to irrigate crops, fill rivers, and supply reservoirs that power hydroelectric plants throughout the country.

Preserving the Amazon is essential for agribusiness – the very sector that devastates the forest – for food production, and for generating energy in Brazil.

Experts warn that up to 65% of the Amazon is at risk of turning into savanna over the next 50 years.

Drought

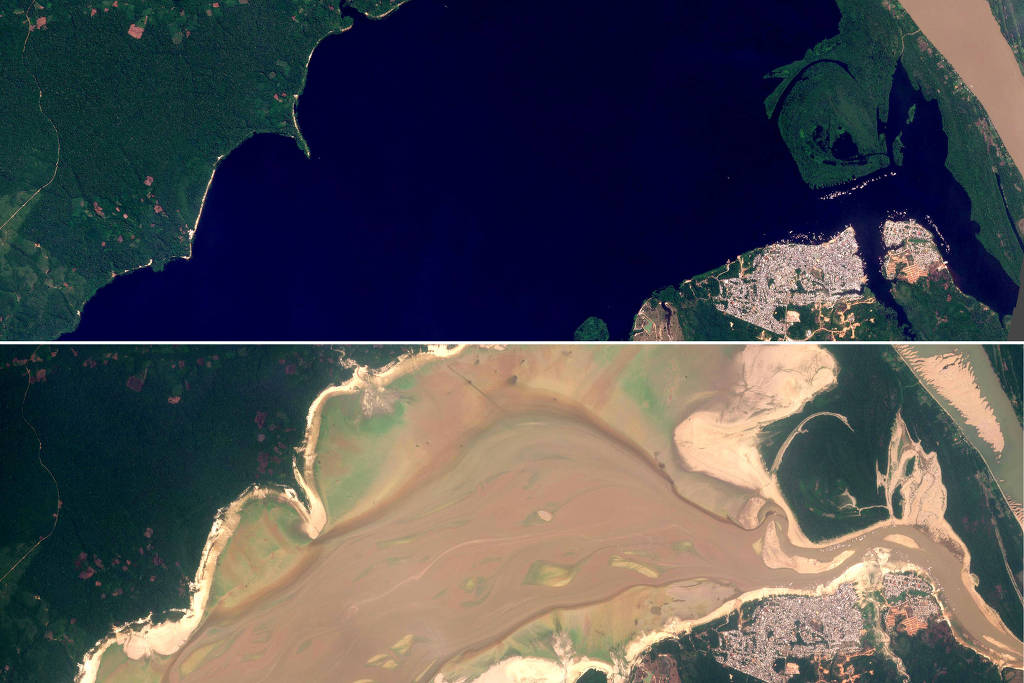

However, the positive result in deforestation reduction is somewhat overshadowed by the scenario of extreme drought that the Amazon has faced in recent months. From July to September, the region has experienced the lowest rainfall levels in the last 40 years. Satellite images vividly depict the speed at which rivers have dried up and disappeared from late July to the first week of October.

A catastrophic situation is unfolding in northern Brazil, as entire cities accessible only by rivers have become completely isolated, having no access to essential supplies such as food, medicine, and clean water. Approximately 500,000 people are already affected in the region with the worst situation in the state of Amazonas where 55 out of 62 municipalities have declared a state of emergency.

The image below shows the Tefé River which flows through a municipality with 73,000 inhabitants. Tefé city reported 154 dolphin deaths in September and October. For riverside communities, obtaining drinking water has become much more challenging as the streams have turned into heated sandbanks. As a result, residents have had to shoulder the burden of carrying water containers and bottles transported from the city.

In recent weeks, there has been some rainfall in the region and some rivers have managed to recover part of their flow. However, this is not enough to help the world’s largest freshwater river rise again as the Amazon River continues to maintain extremely low levels – 12.96 meters on November 17.

Indigenous people who rely on hunting and fishing share the struggle of survival in the forest. Marcelo Karanai, the chief of a village located in Autazes along the Rio Negro, has witnessed indigenous people losing their independence and culture due to the drought in the Amazon.

“We end up getting scared. You look at the vastness of the river and see only land. There was nowhere to run. Whichever way you ran, it was fire and drought” he said.

As if the drought was not enough, wildfires have shown no mercy to the world’s largest tropical rainforest with 7,000 fire outbreaks in the last month. The smoke has even blanketed the capital of Amazonas, Manaus, which is experiencing some of the worst air quality on the planet. Visibility is low and indigenous people are suffering from respiratory illnesses with breathing becoming extremely difficult.

“The reserve, the forest, no longer provide for us unfortunately. Even hunting, which we depend on in the forest… Fishing is not possible either, but hunting has been greatly affected by the wildfires. Many times we cry without wanting to,” laments Marcelo.

El Niño

Experts blame the widespread disaster in the Amazon on El Niño. Two years ago, above-average rainfall caused the Rio Negro to reach its highest level in the last 120 years, leading to flooding in interior cities of Amazonas that lasted for months. Now, the opposite is happening – extreme drought is reducing the flow of major rivers with the Rio Negro currently marked at 13.59 meters – the lowest level since 1902.

El Niño is a climatological phenomenon characterized by an above-average warming of Pacific waters near the Equator. It affects the entire world, causing changes in wind patterns and the distribution of rain and a surge in global temperature. In Brazil, it leads to increased precipitation in the South and drought in the North.

Impact on the Amazon rainforest

According to experts, such intense contrasts in a short period demonstrate that the Amazon is already feeling the effects of the crises highlighted at annual environmental meetings – the world will increasingly experience alternating extreme events, feeling the impacts of climate change. In the Amazon, however, the effect is much more significant due to deforestation and constant wildfires.

“This is just the beginning. The planet is literally on fire, and we have the collapse point of the Amazon approaching. The Amazon will be destroyed even without deforestation because global warming will destroy this forest, creating a cycle of collapse,” predicts Marcio Astrini, Director of the Climate Observatory.

Edegar de Oliveira, Director of Conservation and Restoration at WWF-Brazil, echoed that environmental imbalance could push the Amazon Forest to a point of no return, where rivers and trees will not be able to recover.

“The combination of climate change, El Niño, and rampant deforestation contributes to the worsening and prolongation of the drought which, in turn, leads to an increase in wildfires, further exacerbating the effects of the dry spell. This impacts not only the lives of local people but also affects the economy and water security in other regions of the country, as what happens in the Amazon interferes with other biomes,” stressed Oliveira.