South America, a continent that exports grains and ores across the globe, has one of the smallest railway networks in the world. In the last seven decades, the length of the network has contracted year after year due to poor investment and the lack of maintenance and new projects. In 1965, the continent had 103,000 kms of train tracks whereas currently there are 76,000 kms, according to ECLAC, the United Nation Economic Commission for Latin America.

Latin America is composed of 33 countries but not all of these have a rail network with only 18 having some kind of railway infrastructure in operation.

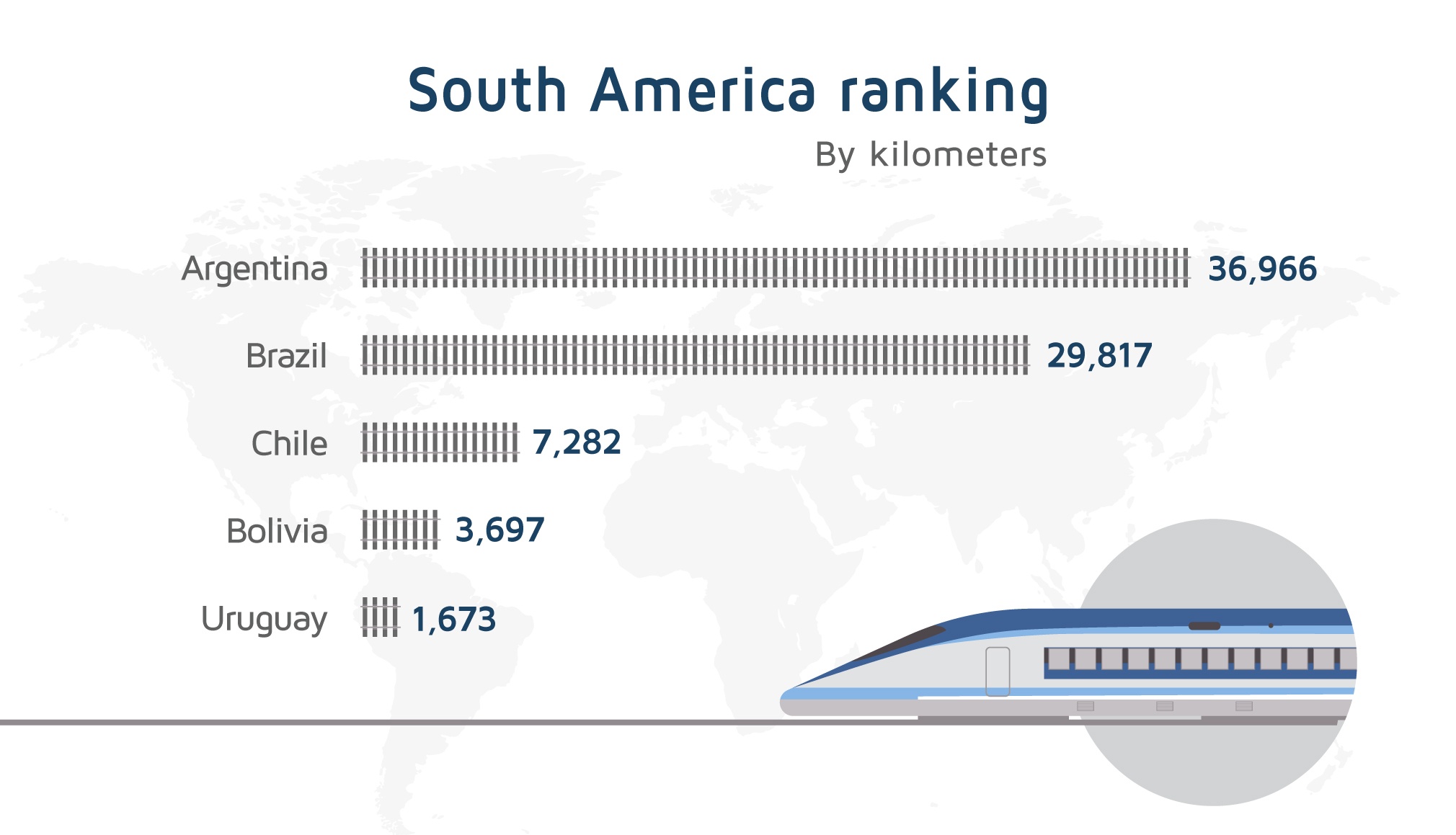

Top 5 countries by railway length

Argentina has the largest network on the continent, with 36,966 kms, according to UIC, the Worldwide Railway Organization. Brazil, despite being the largest country in terms of territory, takes only in the second position with 29,817 kms of track, 9,000 of which are out of operation.

Source: UIC (Worldwide Railway Organization)

Railway overview

According to a study by UIC, the region suffers from a lack of continuity and poorly developed railway systems which jeopardizes the connections between regions of the same country as well as lines that cross the entire continent that could facilitate the transport of both cargo and passengers.

“If they exist, some have deteriorated, are outdated, or closed due to various reasons. Regulations, infrastructure, rolling stock, and procedures in Latin America are not homogenous, all contributing to more complex border crossings in regions where the infrastructure exists. This discontinuity has a severe impact on effective logistical chains, time consumption as well as costs,” emphasized the study.

Many regional links are often missing. Brazil, for example, had more than 36,000 kms of active roads until the 1980s but, in the last six years, it has lost 6,000 kms of connections due to a lack of conservation and the abandonment of transport structures.

“In the case of Europe, the United States and China, these nations see in the railways not only economic opportunities, with tourism ahead but also the chance to reduce their respective greenhouse gas emissions,” explains José Manoel Ferreira Gonçalves, President of Ferrofrente.

Lack of investments

Examples such as Brazil are explained by the low rate of investment in infrastructure in the region. Currently, only 3% of the region’s GDP is channeled towards vital transport and logistics projects, according to the United Nations Commission for Latin America (UNECLAC) whereas the recommendation is 6% and one of these gaps is the railway system.

The national railway network grew until 1957 when it reached its greatest coverage of 31,000 kms. Since then, there has been stagnation and the country has become hostage to road transport which is also precarious with only 12% of roads being paved, according to data from the National Transport Confederation.

“In a train car, load is placed for two or three trucks. A very large number of trucks are removed from the roads with only one train. If this is done in a reusable way, in addition to reducing emissions, it reduces fuel consumption,” explains José Manuel.

Private investments in Brazil

In Brazil, the government is trying to draw inspiration from the models in the United States and Canada to privatize the sector. In order to increase investments, the Brazilian Congress approved a new bill in August this year that authorizes new stretches of railway to be built based on the needs of companies and private groups.

Last week, ANTT, the body responsible for regulating the sector, approved five projects for the construction of new stretches which together should add investments of nearly US$10 billion in Brazil. Another 10 projects are under analysis by the agency as part of the Brazilian government’s goal to double the railway network in the next decade.

“It is a return to the past to try to reach the future. It means that, from now on, entrepreneurs who want to undertake a railway can request and ask the State to build a railway, make the railway segment, and start operating under an authorization regime. It is a return to the past because in the 19th and 20th centuries, Brazil had a rail boom through authorizations, and so until today in the United States, it is the same thing we are doing now,” explains Tarcisio de Meira, the Infrastructure Minister.

An almost forgotten project

South America has an old dream for the sector – a bioceanic railway that would link the ports of Brazil on the Atlantic Ocean to the maritime border of the Pacific Ocean in countries like Chile and Peru. It is estimated the project will cost US$40billion but it is forecasted that this logistical corridor will have the capacity to raise US$1.5 billion per year in exports of meat, sugar, soy bean and leather.

The original idea was that the route would cut through the Brazilian Amazon region but this project was then totally paralyzed for more than 10 years which generated criticism at meetings of Mercosur, the economic bloc of countries in South America. Following a number of misunderstandings among the countries involved, a new proposal has been tabled to link the two parts of the continent by a new route from the southern region of Brazil, at the Port of Paranaguá, to Antofagatta on the coast of Chile.

“This route can be easily covered in three days with ease. This means for the producer a saving of 14 days, avoiding the continent’s contour, either through the Panama Canal or the Magallanes contour. In terms of freight, we will have an average economy of US$700 for a 20-foot container, comparing the cost of exporting through the port of Santos to Shanghai, in China, with that from Antofagasta, in Chile, to Shanghai,” explained João Carlos Parkinson, Career Minister at the Ministry of Foreign Relations in charge of negotiations with neighboring countries.

China investments

For projects such as the bioceanic railway to be able to get off the ground, South America is relying on heavy investment from Chinese businessmen. Since 2002, Chinese entrepreneurs have shown interest in partnering with local companies to invest billions of dollars in the transport sector in South America.

However, most of the proposals faced obstacles, especially in the design phase, and were cancelled mainly due to the lack of environmental licenses and opposition from certain communities. The projects were concentrated in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, and Venezuela. Of the 150 proposals submitted by investors, only half were followed through, according to Inter-American Dialogue.

In May 2015, for example, former Brazilian President, Dilma Rousseff, received Li Keqiang, the then Chinese prime minister, and on paper agreed US$50 billion for the construction of Bioceânica. Six years later, Dilma was impeached and the bioceanic railway is a reflection of China’s investments in Latin America over the last two years: grandiloquent plans, high investments but timid achievements.