On 17 June the world commemorates Desertification and Drought Day with the focus on how to turn degraded land into healthy land. For this occasion, DevelopmentAid enjoyed an exclusive conversation with a Portuguese farmer who breeds livestock in a unique agro-silvo-pastoral Mediterranean forest system called Montado. He shared the story of his farm where he had encountered difficulties in land management before, he learned about regenerative agriculture in the agro-silvo-pastoral model and also revealed some insight into how to produce in harmony with nature.

Desertification is not about deserts

The UN General Assembly declared Desertification and Drought Day in 1995 to raise awareness of this serious issue as the pace of land degradation over the previous decades had accelerated, “reaching 30 to 35 times the historical rate.” The organization explained that the term ‘desertification’ does not refer to the expansion of existing deserts. The phenomenon is due to the overexploitation and inappropriate use of the dryland ecosystems that cover over one-third of the world’s land area.

Agro-silvo-pastoralism to tackle land degradation

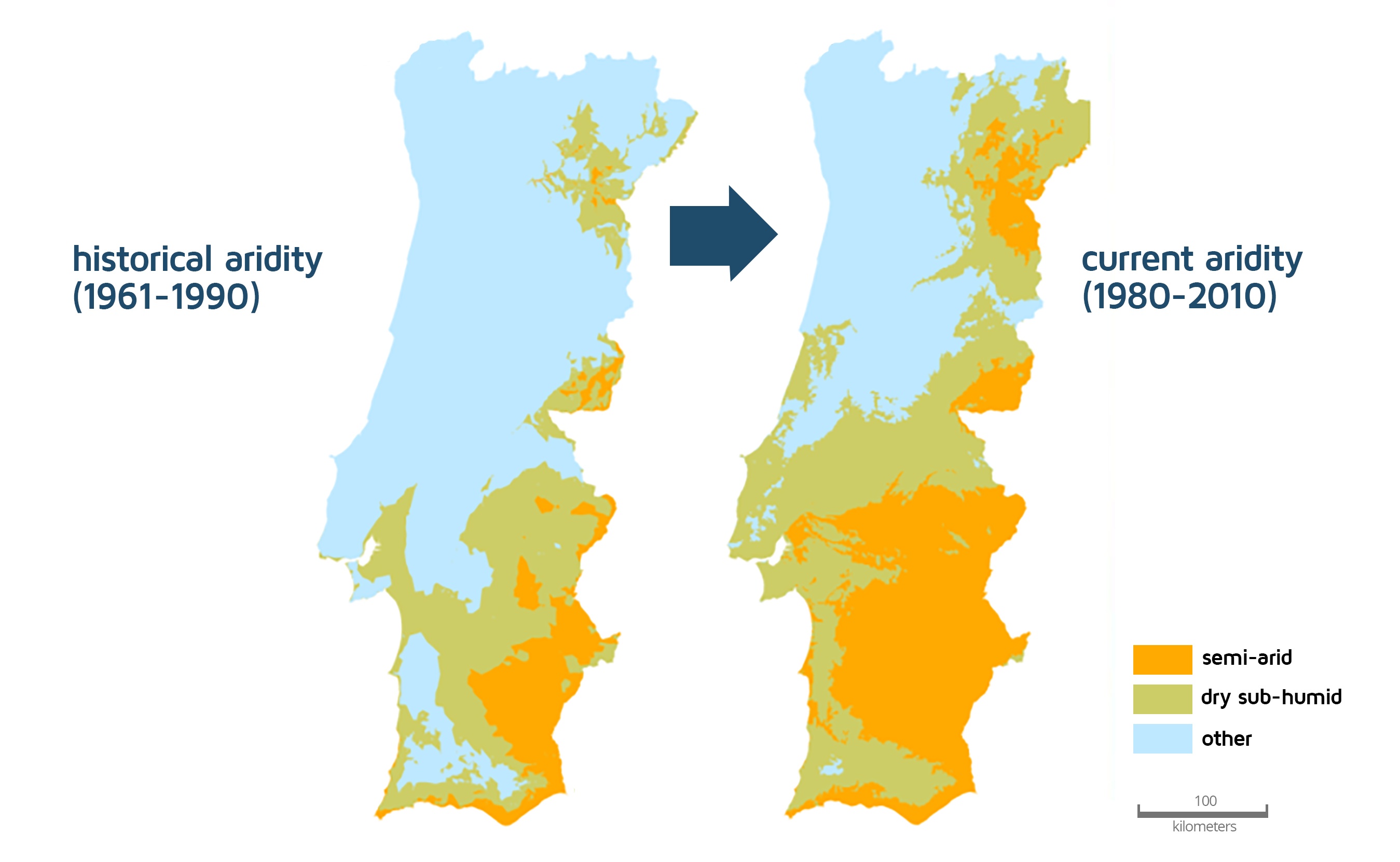

Portugal, at least partially, is in a dry sub-humid area and is one of the countries that faces threats such as land degradation and desertification and therefore the traditional agroforestry system of Montado has been gaining attention among local producers. This system is characterized by a combination of agricultural or pastoral activity and cork oaks/holm oaks planted at low density and represents a High Natural Value farmland.

Montado is a type of agroecological agroforestry where local species of oaks protect the soil, help to retain water, and maintain a cool micro-climate – which all help farms to become more resistant to drought.

Moreover, “forests and agro-silvo-pastoral systems in drylands play crucial economic, social and environmental roles, including by improving the environmental sustainability and resilience of wider landscapes” (FAO)

Regenerative agriculture increases farm efficiency

An example of a farm that successfully uses agro-silvo-pastoralism is the family farmstead, Herdade de S. Luís – Porcus Natura, located in the Alentejo region of Portugal. Spread over 700 hectares, two people manage the land and the livestock which currently comprises 250 cows, 120 sows, 50 sheep, and 70 goats.

In an exclusive conversation with DevelopmentAid, Francisco Alves, the farmer owner of Herdade de S. Luís shared how five years ago following the visit of an expert as well as a master class with Joel Salatin and Darren Doherty he was prompted to turn to regenerative agriculture and transform their farmland into a well-managed Montado system. It was by chance that a technical expert from aleJAB, a branch of the Savory Institute for the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa, had decided to visit the farm and saw the potential to take it to the next level.

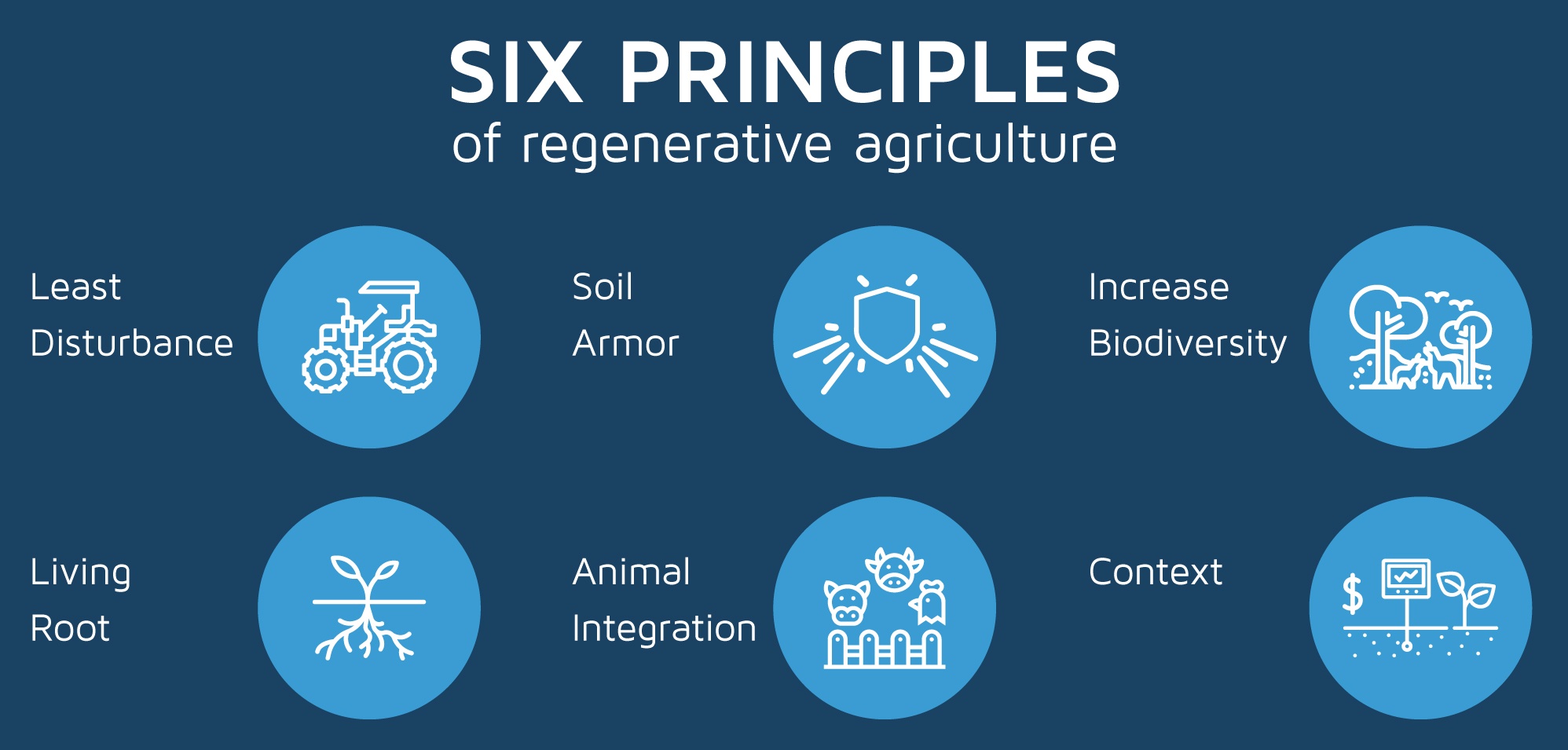

The regenerative model is based on six principles: (1) least soil disturbance with minimum or no-till, (2) keeping the plants’ living root, (3) always have the soil covered, (4) integrate animals into the system to help with nutrient cycling, (5) increase biodiversity and (6) develop the agroecosystem according to the given context – climate, vegetation, type of animals and even finances.

Francisco recalls that their family had always tried to protect the soil, avoid the use of pesticides or synthetic fertilizers and keep the animals outdoors as much as possible. However, the grazing management was far from optimal which would sometimes be reflected in low amounts of food for the animals that in turn affected their health and reproductive capacity.

“Our grazing management system wasn’t so efficient as it is now,” says he.

He emphasized that the added value of the regenerative approach is grazing efficiency which involves learning how to plan rotational management to give more time for the land to recover and, as a consequence, to have more grass for the animals to graze on.

“We are trying to improve the rotation by arriving later to the plot, so that means more rest for the soil so, more feed for animals,” says Francisco.

Francisco explains that if they leave the animals, for instance, cows, too long in any one place, they eat only the type of grass they like while all the other plants would continue to grow thus creating a misbalance in the system which then affects soil health. Francisco moves his cows every day to different plots whereas the sheep, goats, and pigs can graze among them or move to the same pasture after the cows have gone.

Another aspect of efficiency is maximising the use of the available resources and therefore managing the farm in a ‘smart’ way. Before applying the principles of RA, there were only cows and pigs on the farm but, over time, as Francisco learnt how the system worked, he realised that the diversity of the ecosystems on the farmland would allow them to keep lambs and goats too.

“Our land is heterogeneous which means there are different ecosystems. We have low planes with few trees. We have many water lines, then areas with more trees and slope,” explains Francisco.

As a matter of fact, the introduction of goats helped to manage the areas along the water lines that were covered in grass and had to be ploughed by a tractor. Now the goats feed on the grass and so heavy equipment is no longer required. Sheep have also added value to the system as they feed on the dry grass that the pigs leave behind. Increasing the livestock has obviously generated more meat but there are still only two workers on the farm.

Apart from meat, Francisco also produces cork and has 25 hectares of hay for winter feeding and a plot with a mix of crops (grain, pumpkin, herbs) that are added to the animals’ diets in the summer thereby reducing the costs related to external inputs. Francisco confirms that they are becoming more and more self-sufficient in terms of feed for animals.

See also: Agroecology: an opportunity for fragile farms

External inputs can include not only feed for the animals but also the animals themselves. In the case of Herdade de S. Luis, since their initial introduction, no animals have been bought in from outside as they are all bred on the farm. Rotational grazing, a regime that involves the rotation of grazing animals through two or more pastures, allows animals to spend most of their time outside and has a very positive effect on their wellbeing and health. Producers have noted that it has helped them to phase out the need for vaccination and the use of anti-parasitic products with the former causing abortions and other health problems and, as a result, increased the cost of production. Anti-parasitic products also have a serious negative impact on the soil as they deprive it of the microorganisms that are important for soil biodiversity.

All this helps to protect the soil which is the foundation of sufficient nutritious feed for the animals and also allows the farming family to receive financial assistance as they have become a certified organic farm. Francisco stresses that ‘although bio is good, it doesn’t necessarily mean that you work well to regenerate the soil.’

“We are constantly learning and becoming more efficient, and consequently less dependent on off-farm inputs,” emphasizes Francisco.

The producer added that together with the local butchers and chefs, they are able to raise awareness among consumers, thus selling animals with an added value. They explain to the customer how regeneration works for each species and the added nutritional value of pasture meat.

Knowledge of the system

Despite a range of courses that the farmer attended to learn about RA with the main one being at the Savory Institute of holistic management founded by Zimbabwean ecologist, Allan Savory, he points out that RA is not a one-size-fits-all solution.

“For regenerative agriculture, there is no recipe. You have to learn by doing according to your specific context and the environment that you have. Even my neighbour can have a system that differs from mine just because let’s say he has less trees on his plot,” explains Francisco.

The farmer added that courses do offer a good foundation and, moreover, he is part of the larger RA community that allows him to constantly exchange experience and knowledge with others. Most important, however, is to learn from nature:

“It is not about big knowledge or huge studies. It is simply working with nature, observe the result of our decisions and then harness what nature gives you, instead of working against it,” concludes Francisco.