Education is a powerful tool for change yet, in Egypt, many girls face barriers that force them out of the classroom and into early marriages. Despite significant investments in human development, the societal and economic factors that fuel school dropouts among girls after preparatory education remain unresolved and create a ripple effect on their future opportunities and the nation’s progress.

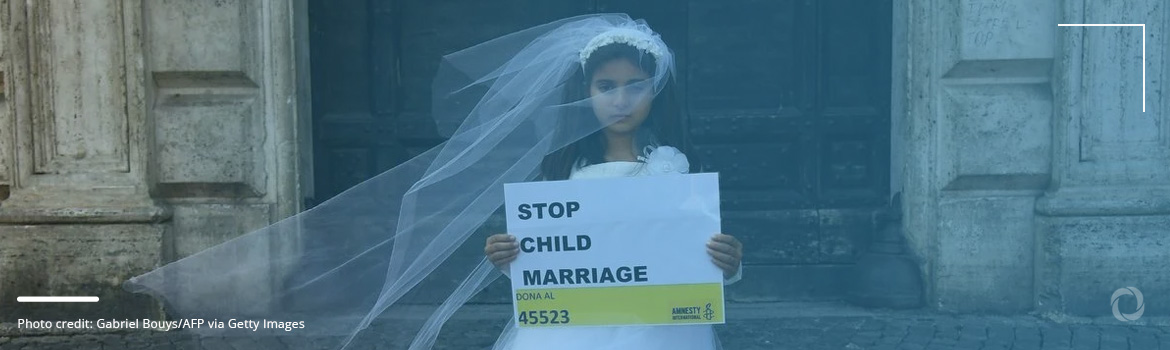

10-year-old brides

While overall dropout rates at the preparatory level stand at 0.87%, with 43,351 students leaving school annually, these figures hide the disproportionate impact on girls, particularly in rural areas.

Early marriage itself is a significant driver of school dropouts. According to the latest study on early marriage, published by the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS) in March 2021, more than 117,000 girls aged 10 to 17 were married. Of these, approximately 36% dropped out of school, and about 40% were illiterate.

The study also revealed that 25% of these early marriages were the primary cause of educational abandonment. This data underscores the extent to which early marriages not only end educational aspirations but also perpetuate cycles of illiteracy and limited future opportunities for girls.

“A girl’s destiny is marriage”

Cultural norms often dictate that a girl’s role is confined to the household.

“In deprived cultural settings, families encourage girls to abandon basic education, believing their place is at home,” Hassan Shehata, an educational expert, told DevelopmentAid.

Mervat Shibl, a 20-year-old from Kerdasa, the largest village in Giza Governorate, is the third of five siblings. Due to rising living costs, their father decided to limit his daughters’ education to the preparatory level. Mervat and her three sisters did not object, understanding that in their town, educational priority was given to males whereas “a girl’s destiny is marriage”, as their mother continued to tell them.

Mervat left school at 13 and was married three years later, following the same path as her elder sister. She noted:

“Like our relatives, we left school and continued learning textile making in workshops and ateliers. I don’t regret leaving school, but I will ensure that my two daughters complete their education, no matter what.”

Dr. Shehata commented:

“Educating girls is not seen as a top priority by many households in rural areas. Early marriage is highly valued and viewed as a kind of protection,”.

Education as expense rather than investment

He also highlighted the effects of poverty, explaining:

“Education is frequently viewed as an expense rather than an investment in low-income homes. Particularly for girls, it is viewed as a luxury by these households rather than a basic need.”

He continued:

“Stories of successful women in various fields are not being shared enough to inspire and guide young girls”.

He stressed that the problem stems from deeply ingrained traditions and cultural legacies that must be actively challenged to liberate girls and women in order to unlock their full potential.

Insufficient government funding

In June 2023, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi acknowledged the government’s failure to meet the education funding targets mandated by the 2014 Constitution. These targets required the state to allocate 4% and 2% of GDP to pre-university and university education, respectively.

President el-Sisi revealed that providing adequate resources for basic education alone – to meet the needs of approximately 25 million students – would require over approximately US$8-9 billion.

See also: Egypt’s stolen childhood: Millions trapped in child labor

However, the actual spending on health and education combined in the 2024/2025 budget accounts for only 3.8% of GDP. Education alone represents just 2.3% of GDP, with a total expenditure of approximately US$6 billion. Given Egypt’s GDP of US$259 billion, this allocation falls significantly short of constitutional and developmental requirements, according to the functional classification of expenditure in the public budget.

While there is no recent official data available on household spending on education, a 2019/2020 income and expenditure survey by CAPMAS highlighted that the average annual household expenditure on education was approximately US$175, representing 12.5% of total household expenses with urban households spending an average of US$255, or 15.7%, compared to approximately US$114, or 9.2%, in rural areas. This gap underscores the economic pressures faced by families, particularly in rural communities, which further complicate efforts to improve educational access and equity.